THE MIRACLE OF FURORE

05.12.2014 BEST OF THE COAST

It’s formed by a stream, the Schiato, that is dry for much of the year but in heavy rain becomes a raging torrent. Where it meets the sea, the valley suddenly levels out into a deep beach-inlet which is garnished by a scatter of fishing boats and a few simple houses clinging to the rock above. Once, before the coast road existed, the only access route was a stepped mule-path from Furore village, a good two hour’s walk away.

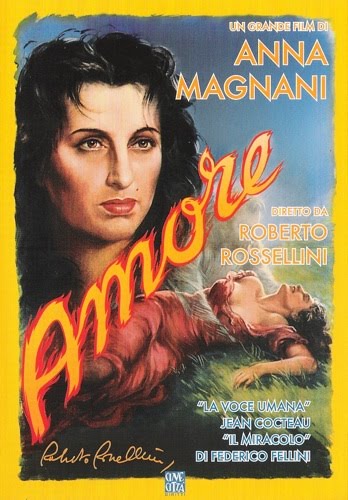

It was here, in what the locals refer to as ‘il fiordo’ – the fjord – that three of the most celebrated figures in Italian cinema turned up in April 1948 to make a film. The director was Roberto Rossellini, who had recently become an international name thanks to the success of his neorealist trilogy Rome, Open City (1945), Paisà (1946) and Germany, Year Zero (1948). With him came his then partner and muse, actress Anna Magnani, and a young screenwriter called Federico Fellini. Still only 28, Fellini had recently graduated from writing humorous sketches for satirical magazines to penning filmscripts – for Rossellini, among others.

Something of a transitional project for Rossellini, the film that the trio had come to the Amalfi Coast to make was the second part of a work of two halves entitled Amore. In this second episode, Il miracolo, Magnani plays Nannì, a simple, gullible local goatherd who is prey to religious visions. One day as she is with her flock, a man dressed in pilgrim’s robes appears. She believes he is Saint Joseph; happy to indulge the illusion, the penniless wayfarer gets her drunk and takes advantage of her. Later, finding herself with child, she assumes she is carrying a miracle baby, but her fellow villagers deride her and subject her to all sorts of cruel pranks. Embittered, she flees society and takes refuge in a cave in Marina di Furore. Finally, when she can feel the birth pangs approaching, she climbs thousands of steps to Furore village, where she delivers the ‘saint’s son’ alone, in an empty church.

On its release in the States in November 1950, under the title Ways of Love, L’amore was accused of blasphemy by the Catholic-dominated lobby group National Legion of Decency. A legal battle followed, going all the way to the Supreme Court. In a landmark decision – popularly known as the ‘Miracle ruling’ – the court recognised that cinema was a form of artistic expression protected by the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of speech.

View

© Roberto Salomone

The hamlet of Marina di Furore is now an ‘Ecomuseum’, its houses, paper mill and ancient hermitages restored to host meeting rooms, a small museum, herbarium and visitors’ centre. In the cluster of houses above the beach, a plaque identifies Villa della Storta, the fisherman’s house that Magnani had bought as a holiday home in 1946 and lived in with Rossellini during the April 1948 shoot. It’s a poignant love-nest, all the more so because, a week or so later, on his birthday (8 May), Rossellini would receive a letter from Ingrid Bergman expressing a desire to work with him – the catalyst for a passionate love affair that would soon drive the director away from Magnani and into the arms of the Swedish actress.

Le Sirenuse Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates on Amalfi Coast stories, events, recipes and glorious sunsets