70 YEARS AGO: LE SIRENUSE BEGINS

19.02.2021 LE SIRENUSE

Photos from the time show a scatter of houses, most of which are still standing today, surrounded by great swathes of terraced gardens and lemon groves. The mother church of Santa Maria Assunta stands out more clearly in these photographs than it does today, as it had so few buildings to compete with.

And yet, Positano was not, quite, cut off from the great wide world outside. A major engineering feat, the famous Amalfi Coast road had existed for almost a century at the time – it was inaugurated in 1854 by King Ferdinand II of Naples. But back then it was still unpaved and – believe it or not – even narrower than it is today.

View

Crucially, though, despite in some ways being a backwater with an economy based on agriculture and fishing, Positano was used to foreigners. In the first half of the twentieth century, it had become a creative haven and place of exile for a small group of northern and eastern European artists, writers, and performers. Many were Russian or German, attracted by the mild climate, the romantic scenery and the freedom from bourgeois values they found in what was then a village a whole day’s journey from Naples.

One such was Michail Semenov, a writer and art dealer who had close contacts with the Ballets Russes and other avant-garde circles (in April 1917, Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau visited his Positano villa just above the beach of Arienzo, in the company of ballet impresario Leonid Massine and choreographer Sergei Diaghilev). Another was Gilbert Clavel, a visionary Swiss writer, set designer and patron of the arts who, in 1909, bought the ancient watchtower that stands guard over Fornillo beach and set about transforming it into a “total work of art”. Later, in the 1920s, a school of German artists – many of them Jewish – settled in the town, while another famous émigré was Lev Nussimbaum, a mysterious writer who originally hailed from Baku and invented an entirely fictitious backstory for himself as the son of a high-born Arab prince.

Running through all the accounts these exiles left of their time in Positano is the kindness and genuineness of ordinary positanesi, who seemed entirely unfazed by this cast of eccentrics that had chosen to live among them. This may have had something to do with their atavistic memories of a time, in the early Middle Ages, when sailors and merchants from Positano traversed the Mediterranean as far as Constantinople. More recently, in the 19th century, many locals had joined the Italian exodus across the Atlantic in search of a better life. So deep down, though most residents were by this time tied more to the land and its produce rather than the sea, and while many had never even ventured as far as Naples, the positanesi empathized with travellers and émigrés.

Nevertheless, until the Second World War, Positano was not a vacation town: it was just too far away from anywhere, and the only places to stay were very basic boarding houses like the Pensione San Matteo. Paradoxically, the war itself would change all that.

View

Originally from Naples, the marchesi Sersale had owned a villa in Positano for many years – that's its terrace in the photo above. For the Sersales, it was a delightful seaside refuge from the city’s summer heat and rich, intense urban life. But during the war, it became more than that: a safe haven, one that (unlike Naples itself) was not about to be bombed or become a battlefield, as it had nothing of strategic importance. The family began spending more and more time there, and three Sersale siblings in particular, Anna, Aldo and Paolo, soon began to consider Positano their home. Paolo was so well-connected and well-respected locally that, in 1944, at the age of just 25, he was elected mayor of Positano – a position he would hold for the next sixteen years. (In the archive photo at the top of this article, he’s shown in the late 1940s, examining a proposed boat jetty with the local priest. The Sersale villa, which would soon become Le Sirenuse, can be seen just to the right of the church dome).

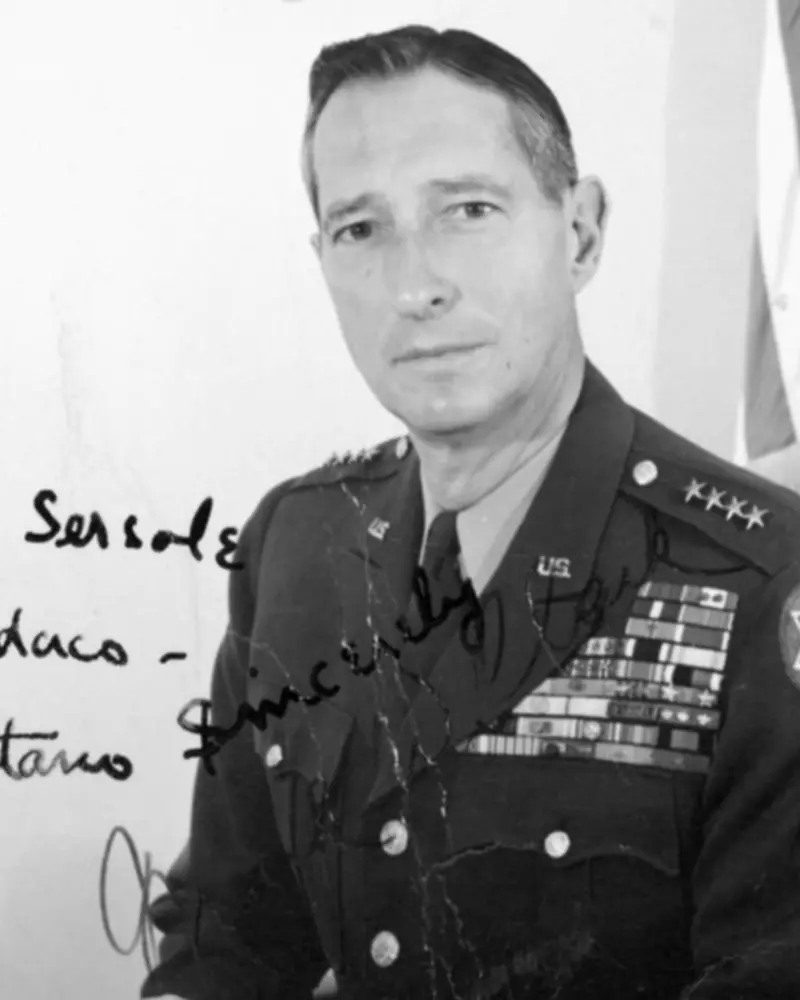

After the Allied landings at Salerno in September 1943 and the capture of Naples in October, the push north was held up by the German Gustav Line at Monte Cassino. Fatigue, both physical and mental, could quickly undermine an army’s morale, so rest camps for soldiers and officers on leave from the battlefront were seen as an important resource. Largely thanks to Paolo Sersale’s influence and the friendship he had established with General Mark Clark of the US Fifth Army, Positano itself was designated as a rest camp for Allied officers, both British and American (in the photo below, Paolo Sersale is seen giving Clark a tour of the town).

View

Private houses, among them the Sersales’ Villa Giulietta, were opened up to war-weary brass hats. But there were problems. At this time, Positano had no running water, and cholera was a constant threat. In an interview he gave to an Italian journalist in 1985, Aldo Sersale recounts that he and Paolo requested a meeting with General Clark, during which they made it clear that if Positano were not connected to the mains water supply, they could not guarantee the sanitary well-being of Allied officers. Clark immediately requisitioned a large batch of 3-inch water pipes, but told the Sersale brothers that he couldn’t spare the manpower to have them connected to the nearest aqueduct, in the hills far above the town.

Luckily, Paolo and Aldo had factored this in. As an official army rest camp, Positano was entitled to receive an army food ration for every inhabitant. By slightly exaggerating the town’s population – from 2,000 to 7,000 – Mayor Paolo was able to pay those who worked on the water supply in food rations, rather than cash. It was a tiny dent in army resources – but it kept the officers and their hosts healthy, put food on local tables, and meant that Positano could finally count on a clean source of water.

After the war, some of the Allied officers who had discovered Positano as a ‘rest camp’ returned with their families. Gradually, the idea planted by Mayor Paolo took root: that Positano, long seen by locals as a rugged, life-on-the-edge kind of place (albeit with its own wild grandeur), was actually something quite unique, a place that foreigners were prepared to face long, arduous journeys to reach, and were in seventh heaven when they did.

So began Positano’s inexorable rise from remote Amalfi Coast village to world-renowned holiday destination. And the Sersales were among the first to realise that the kind of cultured, wealthy, independent travellers who sought the place out deserved to be welcomed in style. Joined by their younger brother Franco, a chemical engineer who would soon embark on an international career before returning to Positano in 1990, Anna, Aldo and Paolo (who had since taken on another important institutional role as president of the provincial tourism board, based in Salerno) decided that their destiny was inexorably linked to the little town. They determined that they would turn Villa Giulietta into a hotel (the two parts of the villa before conversion are on the middle left in the photo below).

Le Sirenuse Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates on Amalfi Coast stories, events, recipes and glorious sunsets