LE SIRENUSE: THE STORY OF A NAME

10.05.2023 LE SIRENUSE

It’s a long post, so for the time-crunched, here are the takeaways:

- Le Sirenuse is the former name of Li Galli, a group of three small islands in the sea off Positano

- The islands are named after the sirens of Greek myth, who lured sailors to their doom with their irresistible song

- The truth behind the myth is that the islands were treacherous obstacles in stormy weather, and in antiquity, many ships were wrecked there

- It was only in the Middle Ages that sirens became identified with mermaids; in Greek and Roman times, they were depicted as part woman, part bird

The Positano villa that our family chose as their buen retiro from the urban sprawl of Naples was originally called Villa Giulietta. However, when siblings Anna, Aldo and Paolo Sersale decided to transform it into a hotel in 1951 – with the blessing of their younger brother Franco, then still at university – they decided the property needed a new name, one that sounded less like a private house.

View

They found it on the horizon. Gazing out from the villa’s beach-facing terrace, the line between sea and sky is broken by three islets that seem to have been placed for maximum scenic effect. Today, their name is Li Galli, but long ago, they were called Le Sirenuse, because of their association with the sirens – mythical creatures whose spellbinding song lured mariners to their doom.

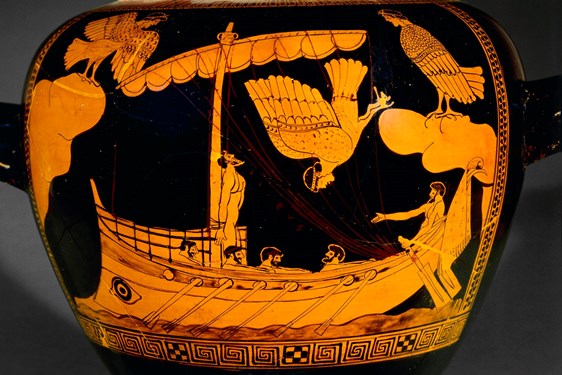

Homer described what they do, not what they look like, in his poetic epic The Odyssey. The sorceress Circe warns Ulysses (a.k.a. Odysseus) that they “bewitch everybody who approaches them… with their high clear song… as they sit there in a meadow piled high with the mouldering corpses of men”. Following Circe’s advice, as his ship approached the Siren islands, and having a great desire to hear their legendary song, Ulysees ordered his crew to tie him to the mast. As the sorceress predicted he would, under the influence of the sirens’ call, he pleaded with his men to untie him, but they ignored him and continued to row past the islands, their own ears stopped up with beeswax.

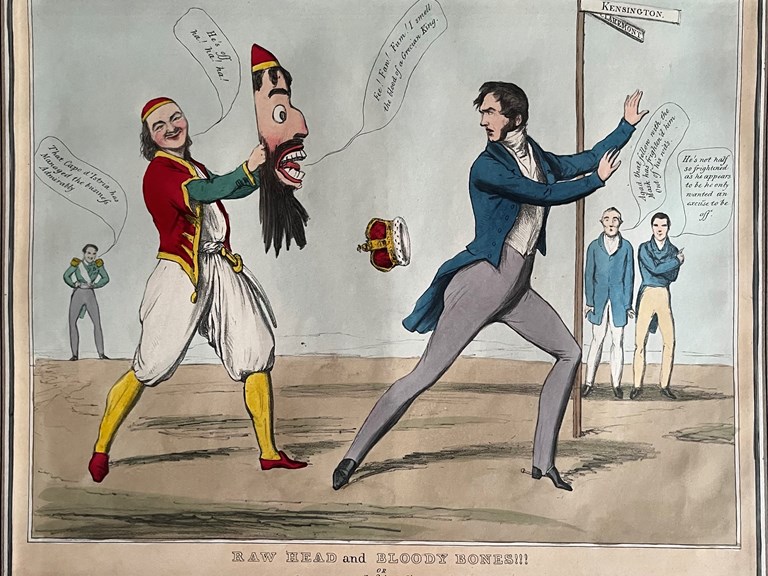

It was left to Greek artists to give the sirens the form that would characterize them throughout the classical era: a fusion of woman and bird. Early on, they were depicted with female heads and bird bodies, while later the whole upper torso became female. The identification of sirens with mermaids came only much later, in the Middle Ages, when the illustrators of bestiaries conflated the classical figure of the siren with the Teutonic legend of the woman who is half-human, half-fish.

View

The most striking representation of the Ulysses scene in classical art is on a Greek red-figured stamnos vase from around 470BC, held by the British Museum. Few of the ancient sources agreed on how many sirens there were; the anonymous painter of this scene opted for three – possibly for reasons of space. Two are shown perched on rocks, their lips parted in song. But the third swoops down, eyes closed. She is not dive-bombing Ulysses’ ship, as might be supposed; instead, she is throwing herself into the sea in despair at these sailors’ apparent indifference to her melodic lures.

This ties in with the story told by the Greek poet Lycophron in his epic poem Alexandra. In his account, the sirens are three sisters called Parthenope, Ligeia and Leucopia. All three drowned themselves, he narrates, when their song was ignored, and their bodies later washed up at different points along Italy’s southern Tyrrhenian coast. That of Parthenope made land on the island of Megaride – later a promontory connected to the mainland – and became associated with the foundation of the city of Naples close to the same spot. Still today, in Italian, partenopeo is an alternative way of saying napoletano.

More than one group of islands along Italy’s southern coast were identified as the home of the Sirens, including Capri’s Faraglioni rockstacks. It was Greek geographer Strabo, in the first century BC, who first nominated the islands that lie offshore from Positano as the home of the mythical temptresses. Sailing south around the Sorrentine peninsula, he wrote, after doubling the headland of Punta Campanella, you will soon encounter “various deserted and rocky little islands, which are called the Sirenusæ”. Their modern name, Li Galli, is a mocking riff on the sirens’ feathered appearance. It means “The Chickens”.

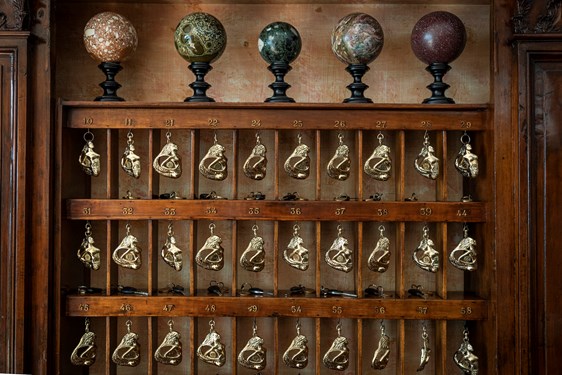

One final ‘siren’ note brings us full circle to an exhibition currently running at the MANN – the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples. In April 1917, Picasso travelled from Rome to Naples in the company of dance impresario Sergei Diaghilev and choreographer Léonide Massine. They were there to present a charity programme featuring Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes at the city’s San Carlo theatre, with all proceeds going to the International Red Cross. But the Neapolitan public was not ready for the dance company’s avant-garde approach. Booked for a five-night run, the ballet gala closed after only two poorly-received shows.

Finding themselves with time on their hands, the artistic trio headed for Positano, where Diaghilev’s secretary owned a house just above Arienzo beach. On their way, they stopped off in Pompeii, where Picasso was enraptured by what he saw. In Positano, it was Massine’s turn to fall in love – with the ’siren’ islands of Li Galli on the horizon. Just seven years later, in 1924, he bought them, and enlisted the help of French architect Le Corbusier to extend the villa that already existed on the largest of the three islands, Gallo Lungo. Much later, in 1989, another Russian ballet celebrity, Rudolf Nureyev, would acquire the island group.

View

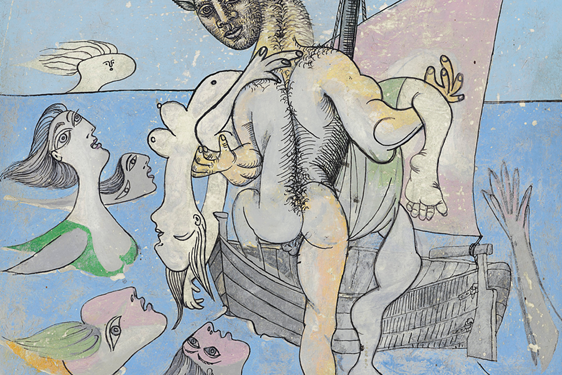

Picasso, meanwhile, channeled everything he saw and experienced in Pompeii, Positano and Naples – including visits to the Farnese collection of ancient sculpture in the archaeological museum, and evenings spent watching a commedia dell’arte theatre troupe – into a fundamental shift in his style and subject matter, from Cubism to a neoclassical style that would become known as his ‘return to order’. The exhibition Picasso e l’antico (Picasso and Classical Antiquity, until 27 August) charts the influence of these two Neapolitan sojourns on this phase of his career, and on the themes that would go on to obsess him in years to come. Among these was that of the bull-headed minotaur (a figure the artist himself identified with) and the siren. Both appear in a remarkable, little-known painting called Baigneuses, sirenes, femme nue et minotaure from 1937 – not in the MANN exhibition – which remained in the artist’s family for decades before finally being sold through Christie’s in 2020. It shows a minotaur-fisherman climbing into a boat with a naked woman in his arms, while sirens with the faces of some of his many lovers – including Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar – look on from the sea.

View

Baigneuses, sirenes, femme nue et minotaure just goes to show what a complex and loaded cultural symbol the siren could become. But at Le Sirenuse, we like to think of the siren-mermaids that have been our symbol since 1951 as strong, proud, independent, fun-loving women, equally at home on land or in the sea, who are not about to drown themselves for any man (they have much better things to do). Long live the song of the siren!

Cover photo Li Galli islands © Ydo Sol

Photo Ulysses stamnos vase © The Trustees of the British Museum

Photo Picasso Baigneuses © Christie’s

All other photos © Roberto Salomone

Le Sirenuse Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates on Amalfi Coast stories, events, recipes and glorious sunsets