LA PASTIERA NAPOLETANA

05.04.2021 RECIPES

Once associated mostly with Easter, it's become so popular today that it's turned out year round by the city's bakers and pasticcieri.

It’s also a kind of final, irrefutable proof of one’s love for the city. If, when spring comes around, rather than chocolate eggs or hot cross buns or white borscht you find yourself craving una pastiera napoletana, you know that Napoli has claimed you for its own.

The taste…

…is difficult to describe. At first it’s the flavouring of orange flower water that dominates – and it’s this, with its strong perfume redolent of certain Middle Eastern pastries, that makes pastiera an acquired taste that many never acquire. But then, as you bite into it, other sensations demand attention. The filling is a kind of baked custard made up of eggs, ricotta, candied fruit and grano cotto, or cooked wheat berries, which give the pie a granular flavour, a little like a rice pudding in which the rice grains have been left just slightly al dente. Italy-based food writer Emiko Davies gets it about right when she refers to the result as “a crazy perfumed cheesecake crossed with rice pudding in a pie”.

A slice of pastiera is a whole meal in itself. If you’re planning to serve it for dessert, you might want to scale back the rest of the menu accordingly. Two lettuce leaves would work just fine.

The history…

…is contested, like much in Naples. It seems certain however that pastiera’s connection with Easter and resurrection is a Christian adaptation of earlier, pagan legends to do with the rebirth of nature after the winter lockdown. And wheat berries have long been associated with the sun – the ancient Greeks used them in their rites to the sun god Apollo, while Sicilians consume them in a kind of sweet porridge called cuccia that is traditionally eaten on Saint Lucy’s day, il giorno di Santa Lucia. Until the Gregorian calendar was introduced at the end of the sixteenth century, this coincided with the winter solstice.

But while the traditions surrounding the pie and its ingredients stretch back to antiquity, pastiera was almost certainly invented in a Neapolitan convent kitchen sometime in the seventeenth century. Even then, however, it was probably not quite the one we're used to. A recipe published in 1692 by Antonio Latini, chef to a Neapolitan grandee, included among the ingredients parmesan cheese, salt, pepper and pistacchios. The version that Neapolitans would today consider to be the authentic pastiera finally appeared in print in 1839 in the appendix to Cucina teorica-pratica, a seminal manual of Neapolitan cuisine penned by master chef Ippolito Cavalcanti.

The recipe…

Serves 12

- 600g/21oz white flour (Italian ‘00’ grade or similar)

- 600g/21oz ricotta (firm, not too runny)

- 500g/17.5oz milk

- 400g/14oz white sugar

- 300g/10.5oz lard or butter

- 250g/9oz pre-soaked grano cotto (wheat berries)

- 100g/3.5oz candied orange and citron peel, diced

- 8 eggs

- 1 vanilla pod

- The zest of one orange

- The zest of one lemon

- One to two spoonfuls of orange flower water

- A little cinammon

Equipment: a 26cm or 10-inch cake tin or high-sided flan case

First, a word about the soaked and cooked wheat berries. Purists insist on doing their own, but the vast majority of Italians who make pastiera at home use pre-cooked grano cotto which is sold in jars and easily available in most supermarkets. Should you wish to do it yourself, soak the wheat berries in daily changes of water for between three and five days, then drain, rinse, and bring to the boil in abundant hot water for around an hour.

There are two parts to making a pastiera: the pastry, and the filling. Start with the pastry. Sift the flour and 150g of the sugar together and rub in the butter (you may want to delegate this to a food mixer) until you have a fine breadcrumb texture. Crack two of the eggs into this and mix then gently knead until you have a ball of creamy yellow shortcrust pastry, which you should cover in clingfilm and put in the fridge for half an hour or so.

Now turn your attention to the filling. First, drain and rinse the grano cotto and put it in a saucepan with 250g of milk, a vanilla pod, a sprinkle of cinnamon and half of the orange zest. Heat on a low to medium flame for around 15 minutes, being careful not to let the milk boil over. Leave to cool.

Round about now is a good time to turn on your oven and set it to 180°C (355°F).

Now put the ricotta in a large mixing bowl, add the remaining 250g of sugar and mix in well. Break and separate two eggs, adding the yolks to the ricotta and sugar and keeping aside the whites. One at a time, add four more whole eggs, beating well each time. Next, add the lemon zest and the rest of the orange zest, between one and two spoonfuls of the orange flower water (depending on how perfumed you like your pastiera), and the candied peel, mixing well.

Whip the two egg whites into stiff peaks and fold them into the ricotta cream with a metal spoon. Finally, add the grano cotto mixture to the ricotta mixture, having first removed the vanilla pod. Some people mouli part of the grano cotto to achieve a smoother filling, but there’s no need to follow suit.

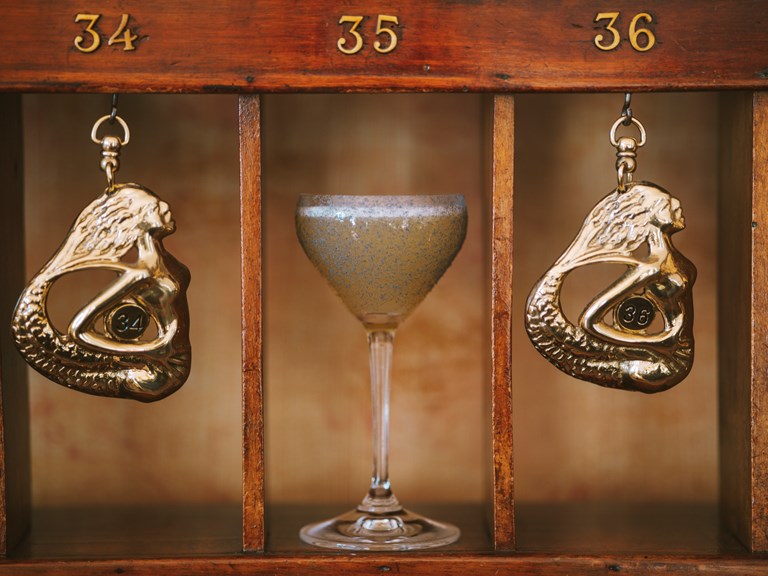

At last, it’s time to take the pastry out of the fridge and roll it out into a circle around 4-5mm thick that will fit your cake tin or flan case, reaching all up the sides. If it breaks or tears a little as you place it in the tin, don’t worry too much: shortcrust pastry is quite forgiving and you should be able to repair the tears and fill in any holes with offcuts. Some authorities suggest rolling out the base and sides separately and joining them in the tin – sure, whatever works. When the tin or case is fully lined, roll out the remaining pastry again to create the strips that will form the lattice on top (around 12 or 14 should be enough, 6 or 7 in each direction). Pour in the filling, and place the pastry strips artistically on top (see photo).

Bake for 90 minutes, until the top is the colour of burnished gold. Now comes the really difficult bit. La pastiera is at its best if left to cool and contemplate the secret of the universe for at least half a day after it comes out of the oven. Our advice is to go for a really long walk or bike ride, and disturb its musings on your return. You’ll have earned it.

Photo © Lee Marshall

Le Sirenuse Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates on Amalfi Coast stories, events, recipes and glorious sunsets