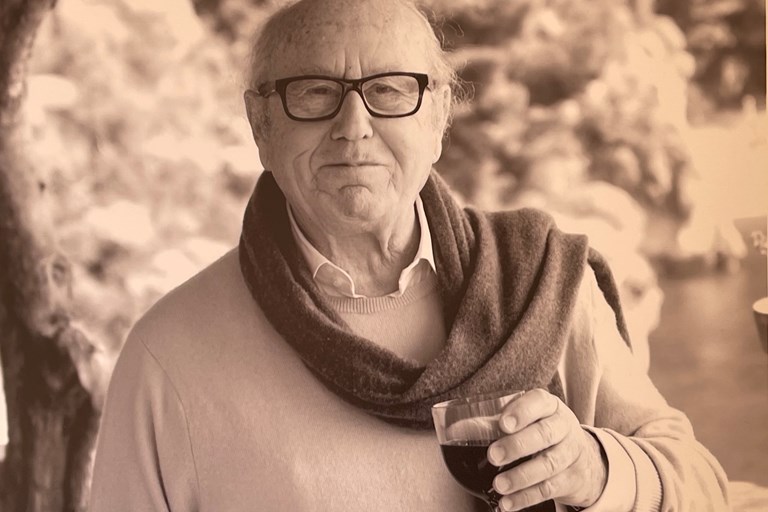

IL GUSTO IMPECCABILE DI FRANCO SERSALE

27.08.2021 LE SIRENUSE

In this fourth instalment of a series of 70th anniversary posts dedicated to the history of Le Sirenuse, we turn our attention to Franco Sersale, the youngest of the four siblings who founded the hotel in 1951. Franco was a chemical engineer whose work took him around the world, so for many years he had very little to do with the running of a resort that he had first known as a child, when it was still his family’s seaside villa and, later, their wartime refuge from the chaos and confusion of Naples.

As he travelled, Franco cultivated two interests that would stand him in good stead when he was called back to Positano in 1990 to help out during the final illness of Paolo, the Sersale brother most involved in the day to day running of the hotel. The first was an interest in decorative art – especially late 18th and early 19th century European furniture, and antique Central Asian textiles. The second was the eye for composition he had developed thanks to his passion for photography.

Franco Sersale left us in January 2015 while on yet another of his far-flung trips – this one a return visit to Udaipur in the Indian state of Rajasthan. Eight months earlier, in May 2014, the Sirenuse Journal’s Lee Marshall had sat down with the then 86-year-old Sersale patriarch at breakfast on the hotel terrace to talk about his curation of Le Sirenuse’s furniture and artworks. Other things got in the way, as they do, and the recording of that conversation languished somewhere in the Cloud for years. The hotel’s 70th anniversary provided an ideal opportunity to listen to it again – and be reminded of what a distinctive voice and vision Franco possessed.

View

Don Francesco Saverio dei Marchesi Sersale, to give him his full name, opened the interview by revealing the simple secret behind his flair for interior design. “I’ve always been interested in looking”, he told the Sirenuse Journal. “If you don’t look, you don’t see anything”.

Franco’s older brother Aldo had found himself reluctantly at the helm of Le Sirenuse when Paolo’s health began to fail. One of the first things this bon viveur and ladies’ man asked his younger sibling on the latter’s return to Positano was whether he would mind taking over the running of the hotel? Franco refused point blank. “I told him I didn’t know anything about hotel management”, he confides. However, one thing he did know, he informed his brother, was that it was time to revamp Le Sirenuse “so as not to be left behind by the competition”. Now this was a job Franco felt he could and should take on. “Aldo had no taste at all”, Franco said with a sigh, “and he commissioned an architect who made a lot of mistakes”.

View

Over the following twenty-five years, beginning with the lobby and restaurant, Franco would transform Le Sirenuse, remaking it in his own elegant, discreet, cultured, well-travelled image. This was no sudden, radical makeover, but a slow amelioration, chair by chair, tile by tile, Suzani wall hanging by walnut console. It was so gradual that loyal guests who came back year after year would be hard pressed to say quite what had changed in their absence – only to concede, a couple of decades later, that pretty much everything had.

Franco Sersale turned his unerring, critical eye on every corner of Le Sirenuse. Some believe that if a hotel’s common areas are impressive enough, the rooms can wait. Not so Franco. He knew every bedroom inside out, and would often sleep in one “just to see what is needed”. Asked about his design criteria in this 2014 interview, Franco answered simply: “I want to make them all like my own bedroom”.

The former chemical engineer had helped to construct modernity around the world, but he was sure right from the start that this was not the right approach for Le Sirenuse. “I think there is no need, at least to my taste, to buy modern furniture, because the time comes when you just want to throw it away”, he opined with his usual directness. The only concession he made to modernism was the hotel Spa, designed by Franco’s architect friend Gae Aulenti and inaugurated in 2001.

Elsewhere, Franco worked on two fronts. One of the things, he knew, that attracted people to the Amalfi Coast was the simplicity and elegance of its traditional houses, the materials they were made from, and the furniture they contained. So he set about not only finding restorers who were able to conserve and refresh the original décor of the family villa that became Le Sirenuse, but also contacting craftsmen or artisanal firms who could seamlessly extend these details with new work done within a traditional idiom.

View

One such was Fornace De Martino, a ceramics company based in the village of Rufoli, in the hills above Salerno, that has been in the same family for more than five centuries. Franco reached out to the company soon after his arrival in Positano to ask if they could match some of Le Sirenuse’s ancient floor tiles, and also reproduce the patterns of some antique tiles he had acquired on his travels. The challenge proved to be a formative one. Tommaso De Martino explains that “until we started supplying ceramic tiles to Le Sirenuse, we’d worked principally in terracotta”. But Franco liked the company’s work so much, not to mention their reliance on two early Medieval kilns, “that he suggested we moved into glazed ceramics in order to make tiles for the hotel of the quality he required”. This is now Fornace De Martino’s principle line of business, and they still have a close relationship with Le Sirenuse (their pearly white floor tiles can be admired at Franco’s Bar, the streetside watering hole inaugurated in the summer of 2015 in honour of Le Sirenuse’s style maestro).

The second direction pursued by Franco in his slow design revolution was to frequent the antique shops and auction houses of Italy and Europe in search of pieces that would work for the hotel. He had a mental list of “missing items” and never bought anything – except perhaps some of the Suzani and ikat textiles he brought back from Central Asia – without knowing exactly where it would end up. As we talked on that May morning, he pointed to two slender, elegant chairs in the La Sponda restaurant vestibule. “Those are the best chairs we have in the hotel”, he informed me. “They’re Neapolitan, from around 1780, and they were inspired by a set of chairs discovered in Herculaneum”. I asked him whether it wasn’t a bit risky to put such delicate chairs in such a public spot… then realized, even before he answered, that he had actually placed them brilliantly, at a point where guests are always walking to or from somewhere. “Nobody sits on them”, he confirmed, “whereas in a bedroom, they would”.

Pretty much all of the pieces and artworks that Franco acquired dated from the same period: “Most of it is from the 1790s to the 1810s or 1820s”, he explained. “But I don’t buy much Napoleonic stuff as I find it too pompous”. He also made some changes to Le Sirenuse’s external appearance, extending the hotel’s iconic Pompeiian red colour scheme – which was already there in the 1930s when the family acquired the villa at the heart of what would become Le Sirenuse – to the walls around the pool terrace, which had previously been painted a shade of yellow ochre.

Franco Sersale pursued beauty and perfection all of his life. But he was also aware that true perfection needs to be worked at, constantly. When the Sirenuse Journal asked him about his black and white photographs – some of which can be seen inside the Spa, as well as in a book, Immagini di lontananze, published in 2001 – he was in self-critical mood. “I’m disappointed with the pictures I’ve taken recently”, he revealed. “I was in Namibia, which is a very beautiful country, and I didn’t take any photos of consequence. Then I got to go back four or five years ago and I took one photo that was worthwhile”.

In the age of Instagram, how many of us are even able to single out the one worthwhile photo from the hundreds we take and post? But it was this demanding pursuit of beauty that made Franco Sersale, and the ambience he created in Positano, so very special.

Special thanks to Michael Maren, one of the guiding lights of Sirenland Writers Conference, for permission to use his lovely portrait of Franco as our headline shot.

The black and white photo above was taken by Franco Sersale while travelling in Bhutan.

The Hipstamatic photo below of Franco Sersale and Jennifer Pastore was taken by Yorgos Kordakis in 2013.

All other photos © Roberto Salomone

View

Le Sirenuse Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates on Amalfi Coast stories, events, recipes and glorious sunsets